Christian apologist Professor Tim McGrew recently defended the historicity of Matthew’s account of the guard at the tomb, in a post put up by his wife, Dr. Lydia McGrew. Professor McGrew’s post was written in response to a challenge he issued to me, in response to my (generally positive) review of Michael Alter’s book, The Resurrection: A Critical Inquiry (2015), which was published at The Skeptical Zone last year. Not wishing to address the bulk of Alter’s arguments, which he considered unconvincing, Professor McGrew challenged me to narrow the focus of our discussion, by listing three of Alter’s arguments which I had found particularly convincing. The first topic on my list which Professor McGrew chose to address was the question: was there a guard at Jesus’ tomb? However, it turns out that McGrew’s argument for the historicity of Matthew’s story of the guard is based on faulty math – a surprising flaw, coming from a man who has written extensively on the subject of Bayes’ Theorem and its role in Christian apologetics. Before we have a look at the math, though, I have a special announcement: Michael Alter himself has decided to weigh in on the controversy, and I have included his remarks in this post.

Curious, that!

Before I continue, let me begin by pointing out four curious facts, which may be of interest to readers.

First, I actually wrote a comment in reply to Professor McGrew’s post, which was never published. Funny, that. Now, I don’t wish to complain about this – after all, the people in charge of What’s Wrong With the World (the blog on which Professor McGrew’s post can be found) have every right to make their own rules, as it is their blog. However, I will note for the record that since the tone of my reply was entirely civil and (I believe) in keeping with the blog’s stated posting rules, I had a reasonable expectation that it would be published.

Second, in his post, Professor McGrew only quoted the first half of my argument, omitting the second half, which I consider to be by far the stronger half. Let me be clear that I am not accusing Professor McGrew of making a deliberate omission, as he subsequently attempted to rectify his omission with a comment attempting to address the second half of my argument. Nevertheless, the original omission betokens a certain carelessness on Professor McGrew’s part: a dangerous failing, when one is engaging in controversy.

Third, the list of three “test cases” displayed in Professor McGrew’s post which we agreed to debate is not the same as the list which I originally provided him. Here is his list of the three topics to be covered:

Since I am unimpressed by Alter’s arguments, I asked Torley to pick three particular arguments as test cases… Torley chose the three following points for this test:

1. Was there a guard at Jesus’ tomb?

2. Did Jesus’ mother and the beloved disciple stand at the foot of the cross?

3. Was Jesus buried in a new rock tomb? (specifically, a tomb owned by Joseph of Arimathea)

However, in actual fact, I offered Professor McGrew a choice of two topics for the first test case: (i) Were Jewish saints raised at Jesus’ death? or (ii) Was there a Guard at Jesus’ tomb?

Professor McGrew then chose the former option, in an early response to my review of Michael Alter’s book. I am therefore a little puzzled as to why he has suddenly changed course, and chosen the latter option instead. Now, Professor McGrew has a perfect right to change his mind, and I presume he has done so for tactical reasons. That is his privilege. Nevertheless, a public acknowledgment of this change of tack would have been courteous to his readers.

Finally, Professor McGrew made no attempt to notify either me or Michael Alter about the post which he had authored. I stumbled on it by accident a short time after he had written it, as I occasionally peruse the What’s Wrong With the World blog for its articles of topical interest. Michael Alter heard about the post from Professor Joshua Swamidass, who thought he might wish to respond – which he did. I hereby invite readers to carefully examine Michael Alter’s response, which I have included in this post. Here it is, in full. Below Michael Alter’s response, I have written my own detailed, mathematical response to Professor McGrew’s defense of the historicity of Matthew’s story of the guard.

=======================================================

CORRECTED and UPDATED RESPONSE TO TIM MCGREW’S “Was there a guard at Jesus’ tomb?” by Michael Alter

Recently, Dr. S. Joshua Swamidass kindly sent me an e-mail providing information that Dr. Tim McGrew had published a guest post response to Vincent Torley’s review of my text, The Resurrection: A Critical Inquiry (2015) in his wife’s group blog: What’s Wrong With the World. First, I am honored that a respected, knowledgeable, and published authority has taken time out of his busy schedule to respond to Vincent Torley’s review of my text. His time is respected.

Now then, let me respond to several points addressed by Tim:

- Tim wrote: Since I am unimpressed by Alter’s arguments…

RESPONSE: Tim is unimpressed of Vincent’s review / summary of my text. His opinion is absolutely respected. However, it is significant that presumably, Tim has not examined my text. At least this is my gut feeling after having read his introduction. In my opinion, if Tim has read my text, he should have made this point clear to his readership. If I am in error, please correct me and excuse me. Therefore, it must be repeated for emphasis that he is only responding to Vincent’s review of my text. Perhaps, it might be harsh, but imagine a movie critic critiqued a movie without seeing it. Or, imagine that a music critic published a review of the Cleveland Orchestra’s performance of Beethoven’s 9th symphony without having heard and seen the actual performance. Finally, imagine that a chess expert analyzed a chess match without having witnessed or seen the chess notations of that match. In the three examples just identified, the evaluation was merely based on an earlier reviewer’s published review. Question: Do you think that the evaluation is fair?

2. It [the guard at the tomb] is mentioned only in Matthew’s Gospel, not in the other three… the argument from silence in such cases is generally terribly weak… As Torley has not attempted to argue that the silence of the other evangelists meets the probabilistic challenge laid out there, I will not belabor the point.

RESPONSE: To the contrary, numerous bible commentators (on both sides of the religious aisle) doubt or question the historicity of Matthew’s account of the guard at the tomb (Dale Allison, C H Dodd, Raymond Brown, R H Gundry, The New Catholic Encyclopedia, etc. On pages 297-299, I offer several “SPECULATIONS” for Matthew’s rationale for inventing the Guard Episode. Although various explanations are possible, I elected to focus on, and explore the rationale discussed by Elaine Pagels. Unfortunately, in my opinion, you did not evaluate her writing.

Most significant, the historicity / veracity of the tomb itself is a point of contention and discussion. On pages 337-339, I identified at least fifteen scholars, theologians, and historians. Numerous times, I include their commentary. Yet, you chose not to belabor the point. Your decision is respected, however, it is NOT fair to my text.

3. Torley objects that the account does not explain why the body could not have been stolen on Friday night.

RESPONSE: On pages 340-343, I specifically presented William Lane Craig’s discussion on this specific topic. After presenting his apologetic, I offer my rebuttal. Your essay responds to Vincent’s rationale, it does NOT respond to my rationale. Once again, this is not fair, and disingenuous to your readers.

4. You wrote: “The third objection is that Matthew’s narrative does not tell us why Pilate would acquiesce in the request of the Jewish leaders.”

RESPONSE: Pilate’s rationale is subject only to scholarly speculation. And yes, you offer several thoughtful ideas on this topic. Thank you! But, these too, are just scholarly speculations. However, here too, these speculations are depended upon the historicity / veracity of a tomb burial. Furthermore, there is scholarly speculation as to the meaning of Pilate’s words: “Take a guard,” or “You have a guard.” That topic, too, is discussed on page 294.

5. You wrote: The fourth objection is that the Jewish leaders would not have asked Pilate to set a guard at the tomb, since it was the Sabbath day, and Jewish law would have forbidden them to hire a gentile to do such work on the Sabbath.

RESPONSE: You added: “First, even supposing the objection to be fairly stated, there is no guarantee that the Jewish authorities would be particularly scrupulous in the matter of hiring a Roman guard to do their work, as they had already shown their willingness to hold a trial by night in prima facie violation of their own rules.” To be one hundred percent honest, this statement makes me cringe. Is it possible that this invented episode (and the trials) is/are, in fact, an argumentum ad hominem against the Jewish leadership (Jewish people)? If you excuse me, you continue the myth of the degradation of the Jewish leadership. I will be the first to admit that not everyone is “wonderful”… And, the Tenakh is clear that numerous times the Jewish people have fallen short of the mark / not been Torah faithful. However, numerous commentators, on both sides of the religious aisle frankly discuss plentiful examples of anti-Semitism recorded in Matthew, and elsewhere in the Christian Bible. Unfortunately, since you presumably (again, I could be in error) have not read my text, you did not comment on pages 343-344. Not to hit a dead horse, but this failure on your part is not fair and it is disingenuous to your readers.

In closing you write: “I conclude that on the first point, Alter’s argument, as summarized by Torley”… This reminds me of a famous quote by the Jewish poet Haim Nachman Bialik. Hopefully, the analogy will be self-evident. “ Reading the Bible in translation is like kissing your new bride through a veil.” Those who understand, will understand…

Take care.

Mike

===========================================================

I’d like to thank Michael Alter for his well-written response to Professor McGrew. I’d now like to address the substance of Professor McGrew’s argument for the historicity of Matthew’s story of the guard at Jesus’ tomb.

A preliminary observation

First of all, I’d like to draw Professor McGrew’s attention to a remark I made, in the same comment where I posed my challenge to him:

In what follows, the question I’d like to address is not whether these claims are true, but whether or not they are probable, when judged on purely historical grounds, by a fair-minded historian with no anti-supernaturalistic bias. [The emphases have been added by me – VJT.]

In his post, Professor McGrew concludes that “Alter’s argument, as summarized by Torley, completely fails to undermine the credibility [of] Matthew’s account of the setting of a guard at the tomb where Jesus had just been buried.” But all that goes to show is that Matthew’s story of the guard is possible, not that it is historically probable. More is needed.

I should also note that Professor McGrew’s post contains no less than four instances of “might have” or “might still have.” Once again, this is not the sort of language one employs when attempting to build a probabilistic case.

So where’s the beef?

Surprisingly, the real substance of Professor McGrew’s argument for the historicity of Matthew’s story of the guard at Jesus’ tomb is not contained within his post, but in a comment he wrote four days later, in response to a critic. Here’s the relevant excerpt:

It is a matter of balancing probabilities and inclining to the most likely. There are three independent variables here: the prior probability that a guard was set, P(G), the probability of our having the Matthean account, given that a guard was set, P(M|G), and the probability of our having that account, given that a guard was not set, P(M|~G). I contend that, on the basis of such information as we actually possess, P(G) is not particularly low, and therefore the ratio P(G)/P(~G) is not significantly less than 1. I have disposed of Alter’s attempt to argue to the contrary. P(M|G) is not itself wildly low; if that is what happened, this is more or less the sort of account we might hope to have of it. P(M|~G), however, is very low; I cannot see why anyone would think it is even on the same order of magnitude as P(M|G). Therefore, P(G)/P(~G) ≈ 1, and P(M|G)/P(M|~G) >> 1; therefore, P(G|M)/P(~G|M) >> 1; therefore, P(G|M) is easily more likely than not.That’s all.

Professor McGrew’s mathematical reasoning is sound, given his three premises, which are that:

(i) the prior probability P(G) of a guard being set over Jesus’ tomb is not particularly low;

(ii) the probability P(M|G) of our having Matthew’s account, given that a guard was set, is not wildly low – indeed, M is something we might expect, given G;

(iii) the probability P(M|~G) of our having Matthew’s account, given that a guard was not set, is very low – in fact, orders of magnitude lower than P(M|G).

In a nutshell: the premises which I contest are premises (ii) and (iii). I think P(M|G) is very low, while P(M|~G) is low, but nonetheless greater than P(M|G) – even on the assumption of an empty tomb.

Why Matthew’s story actually makes more sense if there were no guard

Let’s address Professor McGrew’s premises in reverse order, and start with premise (iii). Why do I contest McGrew’s claim that P(M|G) is massively greater than P(M|~G), while conceding that P(M|~G) is low? Briefly, there are two probabilities we need to consider when looking at the story of the guard in Matthew’s gospel: the probability of such a story being created in the first place, and the probability of its being circulated. The latter is of vital importance, because even a true story will never end up in anyone’s gospel, unless it circulates well enough to reach the ears of the gospel’s author. Now, if there actually were a guard at Jesus’ tomb, then the creation of the story poses no problem: Matthew is simply narrating what actually happened. However, the circulation of a story like the one we find in Matthew’s gospel is extremely unlikely, since it would have been counter-productive for the guards to spread it, as they would have been putting their lives in danger by doing so, for reasons we’ll discuss below. And even if we throw in the additional fact of the empty tomb, and grant that the tomb of Jesus was mysteriously opened while the guards were on duty, one would still not expect them to circulate the story which Matthew claims they did: “His disciples stole the body while we were all asleep.” To quote Alter, “it would have made much more sense for the Sanhedrin to have told the soldiers to say nothing at all or to report that everything was in order and that they had left at the proper time (Schleiermacher 1975, 430).”

On the other hand, if there were no guard at Jesus’ tomb, then there would have been no obvious motive to invent the story of the guard, in the first place. In his book, Alter suggests possible motives, but they are simply that: possibilities. (Incidentally, while we’re on the subject of possibilities, I should mention another interesting hypothesis for the origin of the guard story in Matthew, suggested by Alter in his book (2015, p. 342): “Matthew creatively and skillfully weaves a legendary account incorporating passages from Joshua 10 and Daniel 6 that are supposedly fulfilled by Jesus.” Make of it what you will. All I will say is that the account in Joshua 10:16-27 resembles Matthew’s account in several respects: it features a cave whose mouth is covered up with large rocks, with bodies inside [live ones, in the book of Joshua], and several guards posted outside.) However, once the story of a guard at Jesus’ tomb had been invented (for whatever reason), there would have been no powerful reason not to allow it to circulate freely, as it would have jeopardized no-one, meaning that no-one had any motive to suppress it.

In short: the main hurdle for P(M|~G) to overcome is its creation: why invent such a story in the first place? Once created, however, it could freely circulate. P(M|G), on the other hand, faces no creation hurdle, but a massive circulation hurdle, for two reasons: (a) circulating the story posed a real danger to the guards, who were allegedly the first people to propagate it, since (as we’ll see below) spreading the story put their lives at risk, and (b) the guards would have been better served by spreading another story, instead: “Nothing happened.” Had this lie been too difficult to sustain in the face of contrary evidence, then how about this one: “The earthquake [which Matthew 28:2 tells us was a violent one] broke the seal of the tomb and also caused the body of Jesus to disappear down a crevice.” And even supposing there had been a public clamor for Jesus’ dead body, in order to quell the rumors of its having been resurrected, the guards could have stolen the body of another executed criminal from somewhere (say, a burial pit), and placed it in Jesus’ tomb. Would this have been difficult to carry out? Not at all. We need to bear in mind that according to Jewish religious law, corpses were deemed to be no longer legally identifiable with any certainty if they were more than three days old (see here). The apostles didn’t start publicly preaching Jesus’ Resurrection until seven weeks after the Crucifixion – which means the guards would have had plenty of time to organize their fraudulent scheme, before word of Jesus’ Resurrection got around. There are lots of other stories, then, which the guards could have told, to spare themselves public embarrassment and punishment at the hands of Pilate.

To sum up: the flaw in Professor McGrew’s claim that P(M|G) is massively greater than P(M|~G) stems from the fact that he considers only the probability of the account we find in Matthew’s gospel being created in the first place, while ignoring the much greater problem of its being circulated, initially by the guards themselves, and subsequently, throughout the wider community, over a period of decades.

Is Matthew’s account what we would expect, if there were a guard at Jesus’ tomb?

I’d now like to explain why I contest premise (ii) of Professor McGrew’s argument, that

the probability P(M|G) of our having Matthew’s account, given that a guard was set, is not wildly low: indeed, McGrew thinks P(M|G) might appear reasonably high, if we only had the first part of Matthew’s guard story in front of us (Matthew 27: 62-66), in which the chief priests ask Pilate to give the order for Jesus’ tomb to be made secure. If there actually were a guard, then that’s the kind of historical record we might expect. But there’s more to the story than that. An angel comes down from heaven, rolling away the stone and causing the guards to faint; the guards subsequently report what has happened to the chief priests, who bribe them to spread the story that they fell asleep, and that the disciples stole the body while they were asleep. Once we include this part of Matthew’s guard story, P(M|G) drops dramatically, as it rests on a massive psychological implausibility, which has nothing to do with miracles. Put simply: nobody in first-century Palestine would believe the story peddled by the chief priests, that all of the guards fell asleep at the same time, and none of them woke up while the disciples broke the seal of the tomb, rolled back the stone, and removed the body of Jesus, despite the fact that the penalty for guards falling asleep was crucifixion upside down! That story just wouldn’t wash. Even if there were a guard at Jesus’ tomb, one would not expect an account of the guards behaving in such a silly fashion: first, accepting a bribe, and then spreading a story which would put them all in mortal danger.

At this point, P(M|G) appears to be very low indeed. Let’s have a look at the apologetic attempts to reinflate it.

At the very end of Matthew’s account of the guard, the chief priests try to allay the guards’ fears of being executed on a charge of falling asleep at their posts, by promising to persuade Pilate not to punish them. One commenter on Professor McGrew’s post proposed that the chief priests thought they could convince Pilate to (at least publicly) go along with the false story that they were peddling for public consumption, even though he would have known perfectly well that it was false. This commenter was fair enough to acknowledge the inherent unlikelihood of Pilate listening to the Jewish leaders’ advice and agreeing to “hush up” the issue and let the soldiers live, but then argued that he would have reluctantly agreed to do so, in order to avoid an even greater evil: public insurrection. On the scenario proposed by the commenter, the Jewish leaders may have said to Pilate: “A story that Christ’s followers stole his body will help quell his faction, and a story that some supernatural power overwhelmed the soldiers will foment unrest, so it is in your interest as well as ours to back the version we put out.” Professor McGrew then contributed a clarifying remark of his own, in response to the commenter’s suggestion (emphases mine – VJT):

We are not told whether the move to shield the soldiers worked; we are told only that this is how they were induced to acquiesce in the tale.Many real events seem far less probable on their face than this. The career of Julius Caesar is an instance — or far more incredibly, that of Napoleon Bonaparte. If we were allowed to use uncalibrated personal incredulity as a principle of inference, it would send a wrecking ball through the discipline of history, ancient and modern. Donald Trump, anyone?

So where are we now? Has Professor McGrew succeeded in restoring P(M|G) to the level of reasonable probability? Not at all: the examples he cites merely demonstrate that highly improbable events sometimes happen – like a dead whale ending up in a mangrove forest. But that does not render these events any less improbable.

Professor McGrew also objects that arguments from personal incredulity would undermine the study of history. But the difference here is that Matthew’s account of Jesus’ Passion and Resurrection is not just any old historical account: it is avowedly biased (being written from a Christian perspective), heavily supernatural in its subject matter, and contains what appear to be numerous dramatic embellishments which the other Gospel accounts lack – such as Jewish saints coming to life at Jesus’ death and subsequently appearing to people, or an angel rolling back the stone. I put it to my readers that a responsible historian would be grossly remiss in accepting these accounts at face value. They deserve to be subjected to a more skeptical kind of scrutiny than most other historical accounts. Allow me to quote from the words of a real historian: Dr. David Miano, Lecturer in History at UC San Diego. In his blog article, How Historians Determine the Historicity of People and Events (June 10, 2018), he writes:

Some general rules of thumb that can be used in evaluating a source would be: (1) the closer in time and place that the source is to the historical event, the better. This makes sense, because the longer the gap in time between the event and the writing, the more time there is for the story to be embellished, confused, doctored, misunderstood, or exaggerated. This is not a hard-and-fast rule, because it is possible for a later source to be more reliable than an earlier source, but generally speaking, time allows a story to pass out of memory and to be transformed into legend. (2) separate the core testimony from the biased presentation. Oftentimes the wording that a writer may use to tell a story employs loaded language designed to sway the reader in a certain direction. A historian is wise to wade through the rhetoric to get to the basic witness of the document.When we examine the testimony given in any written source, we first try to ascertain plausibility, and then probability. A claim that is plausible might not be probable, after all.

“A claim that is plausible might not be probable, after all.” Words well worth remembering. And let us add: the scenario we are considering here isn’t even a plausible one: the most one could say is that it’s possible, despite its massive implausibility.

Is there any other plausible way of boosting the probability P(M|G)? The commenter whom I quoted above nominates the publicly known fact of the empty tomb: in his opinion, “the probability that given an empty tomb fact, they [the chief priests] could convince Pilate to allow the theft account to go out for public consumption… is indeed quite reasonable.” But as I’ve argued above, even if the fact of the empty tomb became publicly known, the earthquake would have served as a convenient excuse for the body’s absence. Additionally, it would not have been difficult for the guards to substitute the body of an executed criminal for the missing body of Jesus, had they wished to: they had seven weeks to do it.

One last possible way of boosting P(M|G) is by supposing additionally that Jesus actually rose from the dead, and that an angel rolled back the stone. The flaw in this assumption should be readily apparent to everyone: it assumes the very thing which it sets out to prove: the Resurrection. I am forced to conclude, then, that the attempts to render P(M|G) reasonably probable are all failures.

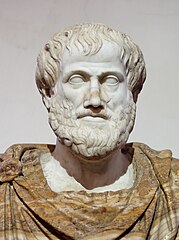

Too incredible to invent: Professor McGrew appeals to Aristotle

In a comment attached to his post, Professor McGrew also chides me for expressing incredulity at an attempt by a Christian apologist (Wenham) who argues from the improbabilities in the story (conceived as a story) that the best explanation for why it is told is that it was notoriously true. As I put it in my review: “Wenham is inclined to credit the story of the guard, precisely because it’s so full of obvious holes that he thinks no-one would have made it up in the first place.” McGrew contends, quoting Aristotle, that I am being grossly unfair to Wenham. But even if I am, that, in and of itself, does nothing to establish that the story of the guard is probably true – a story which Wenham himself concedes “bristles with improbabilities.” Surely a fair-minded historian would take note of these improbabilities, and evaluate accordingly. Once again, I ask: are we to believe Matthew’s claim that the chief priests and the guards (Mt. 28:12-13) deliberately circulated the story that all of the guards fell asleep, which would leave them liable to a capital charge? Is that historically probable?

But let us examine Aristotle’s argument. Does he say what Professor McGrew claims he says in his Rhetoric 2.23.21 (1400a)? Aristotle writes: “For the things which men believe are either facts or probabilities: if, therefore, a thing that is believed is improbable and even incredible, it must be true, since it is certainly not believed because it is at all probable or credible.” This argument deployed here is very similar to Tertullian’s “certum est, quia impossibile” (which is often misquoted by skeptics as credo quia impossibile).

Professor McGrew seems to be interpreting Aristotle as arguing that a claim is more credibly true if it is prima facie incredible, on the grounds that its very incredibility militates against its having been made up: no-one would be dumb enough to make up a story full of holes. With the greatest respect, I don’t think that’s what Aristotle is arguing in the passage quoted above. Instead, I think that the point he is making is that a claim is more credibly true if it is widely accepted (“believed”), despite its prima facie incredibility, as such an incredible-sounding claim is unlikely to be widely believed by men unless it has strong independent support, which nobody can gainsay. As I read him, Aristotle is putting forward something like Nachmanides’ kuzari argument, which features heavily in Jewish apologetics.

Assuming my interpretation is correct, the question we need to answer is: was the story of the guard at the tomb ever widely believed by the Jews? Aside from Matthew’s Gospel, we have absolutely no grounds for thinking that it was. All we know, from later Jewish polemics against Jesus, is that the Jews believed the disciples had stolen his body. For instance, Justin Martyr, in chapter 108 of his Dialogue with Trypho, mentions the Jewish claim that Jesus’ disciples “stole him by night from the tomb, where he was laid when unfastened from the cross, and now deceive men by asserting that he has risen from the dead and ascended to heaven.” But that polemic proves absolutely nothing about the existence of a guard.

So it seems that Aristotle’s weighty authority does not support Wenham’s argument, after all.

Where Professor McGrew and I more or less agree

Professor McGrew will be delighted to learn that I am prepared to concede the first premise of his argument. (I would be happy to set P(G) at 0.1, or 10%, for the sake of argument. Certainly I would put it at more than 1%, after carefully weighing the arguments which Professor McGrew marshals in his post.) Premise (i) is of course predicated on the assumption that Jesus was actually buried in a tomb. I had previously maintained that an independent historian would conclude Jesus’ body was most likely thrown in a common burial pit for criminals, having been influenced by Professor Bart Ehrman’s spirited defense of this view. Since writing my review of Michael Alter’s book, I have examined the literature on the subject more carefully, and I now think the matter is far from settled. Jesus’ burial in a tomb remains a strong possibility, although I continue to vigorously maintain that it was not a new tomb owned by Joseph of Arimathea, as three of the Gospels claim. (Mark’s Gospel doesn’t say if it was new or not.) I would also maintain that John’s account of Jesus’ burial by Joseph of Arimathea (and Nicodemus) is heavily embellished. However, I am now prepared to grant that the prior probability of a guard being posted at Jesus’ tomb, as Matthew narrates, is not as low as I had previously thought.

What prompted my change of mind? Let’s examine some of the key arguments I brought forward in my review of Alter’s book. Professor McGrew has helpfully summarized these arguments under four points, which I have listed below (with very slight modifications in the interests of clarity), along with his responses and my counter-responses. (Of these four points, C and D relate directly to the prior probability of a guard being set over Jesus’ tomb – in other words, P(G).)

A. The guard at the tomb is mentioned only in Matthew’s Gospel, not in the other three. [McGrew’s response: “the argument from silence in such cases is generally terribly weak.”] [My reply: fair point.]

B. Matthew’s account fails to explain why the body could not have been stolen on Friday night. [McGrew’s first response: some scholars have argued that when properly interpreted, Matthew’s account actually implies that the chief priests could have made their request for a guard on Friday evening, which means that if Pilate promptly granted the request, Jesus’ body could not have been stolen on Friday night, after all.] [My reply: the scholars McGrew cites (Doddridge, Paulus, Kuinoel, Thorburn) all wrote in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. Is this the best he can do? In his book, Alter mentions another source dating from 1893, making the same claim, but goes on to note: “Most commentators presume that the visit was held on Saturday morning” (2015, p. 288).] [McGrew’s second response: even if the Jewish leaders had to wait until Saturday to obtain a guard from Pilate, they “might have left someone of their own to keep an eye on the tomb overnight. Failing that, they might still have thought that it would be better than nothing to have a guard set for the remainder of the time period specified” (italics mine – VJT.)] [My reply: McGrew is clearly reaching here. “Might have” establishes mere possibility, not probability.]

C. We are not told why Pilate would agree to the Jewish leaders’ request for a guard over Jesus’ tomb. In particular:

1. The request concerned a purely religious matter, and we would not expect Pilate to care much about such things. [McGrew’s response: “An imposture {on the part of Jesus’ disciples} might well raise civil trouble in Jerusalem… Preventing civil unrest lay squarely within Pilate’s sphere of responsibility. On this count, the matter is exactly the sort of thing we would expect the Jewish rulers to request of Pilate.”] [My reply: if we assume for the sake of argument that the Jewish leaders were actually aware of a rumor that Jesus had claimed he would return to life after his death, then McGrew has a valid point here. However, the assumption McGrew is making here does not enjoy a scholarly consensus: it is possible, but has not been shown to be probable.]

2. Pilate had just been pressured into ordering Jesus’ crucifixion, and therefore any further request would be unlikely to meet with a favorable reception. [McGrew’s response: “The theft of a body and proclamation that the individual in question was alive was the sort of scenario a Roman governor under Tiberius could not safely ignore.”] [My reply: the example McGrew cites to support his case relates to a conspiracy which the Roman Emperor Tiberius feared, against his own life. Jesus posed no such threat, although McGrew could perhaps urge in reply that Jesus was crucified as the “King of the Jews,” making him a pretender in the eyes of Rome, and hence someone whose resurrection would be bad news for Pilate.]

D. The Jewish rulers would not have made such a request of Pilate, since a gentile employed by a Jew would not be allowed to work on the Sabbath. [McGrew’s response: “there is no guarantee that the Jewish authorities would be particularly scrupulous in the matter of hiring a Roman guard to do their work, as they had already shown their willingness to hold a trial by night in prima facie violation of their own rules.” In any case, nothing in Jewish law prevented them from “making a request to Pilate, as the civil governor, that he would secure the tomb with a guard.”] [My reply: the first part of the response naively assumes that the negative portrait of the Jewish authorities in Matthew’s gospel is historically accurate. The second part of the response is more substantial, and makes a valid point.]

When all is said and done, I’m prepared to concede that McGrew’s responses to my foregoing arguments at least show that the prior probability P(G) of a guard being set over Jesus’ tomb is not as low as I had imagined. However, nothing in his responses suggests that this prior probability would be especially high, either. For argument’s sake, I’m prepared to accept that P(G) = 0.1.

Summing up

As we saw above, Professor McGrew’s reasoning was as follows:

“P(G)/P(~G) ≈ 1, and P(M|G)/P(M|~G) >> 1; therefore, P(G|M)/P(~G|M) >> 1; therefore, P(G|M) is easily more likely than not.” I, on the other hand, would argue that

P(G)/P(~G) ≈ 0.1, and P(M|G)/P(M|~G) is considerably less than 1; therefore, P(G|M) is quite unlikely, after all. I leave it to readers to decide who has the better of the argument.

I would like to conclude by thanking Professor McGrew for this exchange of opinions. He is welcome to comment on this post. What do readers think? Over to you.

APPENDIX

The following is an excerpt from Michael Alter’s book, The Resurrection (2015, pp. 340-342), in which Alter proposes a scenario as to how Matthew’s story of the guard might have originated. After presenting this scenario, I’ll briefly examine Professor McGrew’s criticisms of it. I hope this information will help readers form a better evaluation of the probability P(M|~G), discussed by Professor McGrew above – i.e. the probability of Matthew’s account being composed if there were no guard at Jesus’ tomb. Without further ado, here’s Alter’s scenario (emphases are mine – VJT):

…An obvious argument by doubters is that anyone could have removed the body before the tomb is discovered early Sunday morning by the several women. To circumvent this objection, Matthew is forced to invent a guard at the tomb. However, the presence of a guard will require a rational explanation. Consequently, Matthew is forced to invent the account of the Jewish leadership going to Pilate. But when is it possible for this visitation to have occurred? The earliest possible day would have been the Jewish Sabbath. However, a visit by the Jewish leadership on the Jewish Sabbath will have seemed unlikely to most knowledgeable readers or listeners to the text. Consequently, Matthew 27:62 obscures from its readers and listeners that this visitation occurs on the Sabbath: “Now the next day, that followed the day of the preparation, the chief priests and Pharisees came together unto Pilate.” This lie is necessitated because of Mark’s chronology (Mk 15:47; cf. Lk 23:54-56). That is, there is not enough time for the Jewish leadership to return to Pilate before the Sabbath and request a guard.

But why did the Jewish leadership need to see Pilate? There has to be a reason. Consequently, the previous lie necessitates Matthew inventing the idea that the Jewish leadership knew about Jesus’ prophecy that he will rise again after three days, “Saying, Sir, we remember that the deceiver said, while he was yet alive, After three days I will rise again” (Mt 27:63). How the Jewish leadership knew about this prophecy is not provided by Matthew.

Up to now, Matthew has explained why a guard is at the tomb, and he also provides information for his readers and listening audience that the guard stayed there for an undetermined length of time until the women arrive. This scenario now creates an even bigger problem. How can the women examine the tomb and verify that the tomb is empty if it is guarded by a Roman watch? Somehow these Roman soldiers must be eliminated from the scene. To resolve this problem, figuratively speaking, the angel descending from heaven and removing the stone, this terrifying the guard into a state of paralysis, kills two birds with one stone. Matthew has now explained how the tomb is open for the women to verify that Jesus’ body is missing and how the guard became immobilized to permit the women’s investigations at the tomb.

However, Matthew has now dug an even deeper hole for himself. Given that there is a guard at the tomb, why is there no record of what they saw? That is, why is there no record that the guard saw both the angel descending from heaven and the removal of the stone? To take care of this problem, Matthew invents the bribe: “And when they were assembled with the elders, and had taken counsel, they gave large money unto the soldiers” (Mt 28:12). However, this bribe creates yet another loophole. Would all the guards accept such a bribe, knowing that, if they were found out, it would mean their certain execution? Consequently, Matthew needs to invent another lie to protect his narrative. Thus, Matthew 28:14 states that the Jewish leadership will come to their assistance: “And if this comes to the governor’s ears, we will persuade him, and secure you.” [Note: Cassels (1902, 828) posits: “The large bribe seems to have been very ineffectual, since the Christian historian is able to report precisely what the chief priests and elders instruct them to say.”]

In brief, Matthew could have created a better lie. Every time he tells a lie it requires another and bigger lie to cover up the problem created by the previous lie. All these lies are ingeniously interwoven.

Professor McGrew read only my abbreviated version of the foregoing scenario, which did not impress him greatly. Here’s how I summarized it in a single paragraph (see also here):

…Alter suggests (2015, pp. 340-342) that the story was originally created in order to forestall an anti-Christian explanation for the empty tomb: maybe the reason why it was found empty is that Jesus’ body was stolen. To forestall that possibility, someone concocted a fictitious account of the Jewish priests going to Pilate and requesting a guard, in order to quell popular rumors that Jesus would rise from the dead on the third day. But that created a problem: if there were a guard at the tomb, then the women wouldn’t have been able to enter and find it empty. So in the story, the guard had to be gotten out of the way. This was done by inserting a terrifying apparition of an angel just before the women arrived at the tomb, causing the guards to fall into a dead faint, and conveniently providing the women with the opportunity to enter the tomb. And in order to explain why there was no public record of the guard seeing the angel remove the stone, the story of the guards being bribed into silence by the Jewish chief priests was invented. In short: the lameness of the guard story cannot be used to establish its authenticity. The story is an ad hoc creation, designed to forestall a common objection to the empty tomb accounts.

Professor McGrew is having none of it. He writes (emphases mine – VJT):

There is certainly something ad hoc going on in Alter’s treatment of the matter, but the problem lies in the methodology Alter employs here rather than in the story as told in Matthew’s Gospel. Start with a surmise — “Maybe it didn’t really happen.” Faced with the fact that there isn’t much reason to doubt it, make up a purely hypothetical motivation that someone might have had for inventing such a story: “Maybe Jesus’ body really was stolen, and they had to create a cover story for that fact.” Faced with the further problem that this particular cover story is hardly what one would invent to answer to that hypothetical state of affairs and could easily be contradicted by people on the ground in Jerusalem who knew the guards, ignore the problem and instead double down on creating hypothetical rationales for other parts of the story. “The guards have to be gotten out of the way so the women can enter …” Okay, why not just have Jesus’ resurrection itself knock them out instead of resorting to the awkward fabrication of their falling asleep? Simple questions like this suffice to show how specious such reasoning is. What historical narrative, however faithful, could not be dissolved (at least in the imagination of the critic) by the application of such methods?

Professor McGrew asks a fair question: why did Matthew feel the need to introduce an angel, rather than have Jesus himself roll back the stone and in so doing, knock out the guards? The reason, I would suggest, is that the story of the angel at the tomb was already part of the Christian tradition, as it is found in all four Gospels, in some form or other. Even in Mark’s Gospel, the young man dressed in a white robe, whose presence alarms the women, is meant to be an angel (compare with Luke’s description of two men in dazzling clothing). So the logical thing for Matthew to do would be to give the angel a more dramatic role – that of rolling back the stone – and an intimidating appearance (“like lightning”), so that the terrified guards fall into a faint and become “like dead men.” (Matthew does not say that they fell asleep; that was the lie they supposedly agreed to circulate.) So to my mind, Alter’s scenario is not as fanciful as Professor McGrew evidently thinks. It sounds plausible to me. The only caveat I would add is that we don’t know who invented the story: it could have been Matthew, or it could have been some members of an early Christian community, who composed it in to counter objections by hecklers.

Finally, in response to Professor McGrew’s objection that any historical narrative, even a reliable one, could be dissolved by the universal acid of Alter’s fanciful speculations, I would remind him of the point I made above: Matthew’s account of Jesus’ Passion and Resurrection is not just any old historical account: it is biased, heavily supernatural, and contains what appear to be numerous dramatic embellishments. Such an account therefore invites a special kind of scrutiny, which we would not normally subject other historical accounts to.

I shall lay down my pen here, as I have written enough. Over to you, readers.

phoodoo,

Perhaps a rough analogy will help.

Bayesian inference is like logical inference in many respects. Logical inference takes a set of premises as “inputs” and generates a conclusion as its “output”. Bayesian inference takes a set of probabilities as “inputs” and generates an updated probability as its “output”.

The soundness of a logical inference depends both on the validity of the logic and the reasonableness of the premises. The soundness of a Bayesian inference depends both on the correctness of the calculation and the reasonableness of the “input” probabilities.

A logical inference from bad premises may produce an incorrect conclusion, even if the reasoning is done perfectly, but that isn’t an argument against making logical inferences. Likewise, a Bayesian inference from unreasonable probabilities may produce an unreasonable updated probability even if the calculation is done perfectly, but that isn’t an argument against making Bayesian inferences.

What is number two reason to doubt the Resurection?

So, summing up on where the disagreements are, nobody seems to dispute that statistics is a useful and productive branch of mathematics and an important tool in hypothesis testing.

So could we concentrate on my question 1 for a moment?

1. Can we use probability theory to help decide historical claims, in particular whether Jesus’ tomb was guarded?

Bearing in mind that the only account we have of the events is in texts that, at the earliest, were written a generation later, in scholarly Demotic Greek, by a person or persons unknown, with motives we can only guess at and with no corroborating material from archaeology or other contemporary texts, how can we test our assessments of the likelihood of these events. Keiths says we do it all the time “informally”. That’s a much weaker claim than putting numbers to it, which is how I read Vincent.

So I suggest the burden of proof is on anyone who can formalise a probability estimate of the likelihood that the dead body of Jesus was placed in a tomb and guarded by some people tasked with the job. Show me the figures and how you arrive at them. And then how do you demonstrate they have any usefulness or meaning, whatsoever?

walto,

We have to be careful not to dismiss the details a priori on the basis that the story is fictional. That would leave us open to circular reasoning. What I am trying to do is to draw parallels between various texts handed down to us from antiquity. If we want to draw conclusions about the veracity of events reported in such texts we need to be consistent in our methodology. I see massive differences in how believers in the Bible judge the reliability of that text and how they judge the reliability of, say, the Iliad. I haven’t really seen much critical thought from their side on why that is.

I’m inclined to doubt the usefulness of probability theory here.

Human behavior tends to be chaotic, and history is often concerned more with specific events than with statistical trends.

Neil Rickert,

I’ll put you down as a “No” then. 🙂

And you avoided answering the questions because you knew I was right.

How do you know that?

/FFM

It’s a bit of a problem, sometimes getting folks to answer questions. I’m not doing too well. Have you an opinion on the usefulness of probability theory as applied to specific events recounted in the Bible?

keiths,

None of this helps VJ’s plea that you can assign numbers to a presumption that an event occurred. You can call it an epistemic problem, or a metaphysical problem, or whatever and that changes nothing. Its not numbers, it hunches. Hunches aren’t right or wrong, so VJ can’t claim to dispute the math. There is no math!

phoodoo,

There are hunches and there are hunches. In my old line of work, hydrocarbon exploration, we actually do assign numbers to our estimates of certain aspects of the subsurface, most of which are driven by historical events.

For instance, one element we need to risk is the quality of the oil reservoir (which is not the same as the presence of an oil reservoir). Quality here means the physical and chemical properties that allow the hydrocarbons to flow through the rock and into the well. These properties are the result of historical processes that have taken place during and after the rocks were deposited.

We evaluate our data and apply our judgement, driven by geologial knowledge and experience. Usually we do this is a team to try and prevent individual bias. This judgment is first expressed qualitatively, in terms such as “highly likely”, “somewhat unlikely”, and so on. We then assign numbers to these qualitative statements: Highly Likely would be 80%, Somewhat Unlikely would be 40%, etc. (for example).

We need to do this because we have to multiply the probabilities across a number of factors that, all combined, go towards giving us an overall prospect risk. Since you can’t multiply a “highly likely” situation with a “somewhat unlikley” one, we need to translate these judgements into numbers that we can multiply.

The end result of multiplying all (usually six) factors is the overall prospect risk. Of course this is not a ‘hard’ number, but it is an expression of the totality of our data, analysis and technical judgment. The number (Probability of Success or PoS) is used to run economics to support the drilling decision. A such, the PoS is of great value in ranking a portfolio of prospects to help decide where to prioritise funding.

In most Companies there are people who analyse the results of many wells in hindsight to try and see if these estimates were generally in the right ballpark. This will allow people to (re)calibrate their estimates in the future, for instance if it turns out that over a large number of wells the Company tends to underestimate the reservoir quality risk.

To me the question here is not so much if we can assign probabilities to historical events, but to figure out if we have enough information to meaningfully do so. This is a separate judgment that should be made before we even start assiging the qualitative probabilities. If you have barely any data your judgements are pretty meaningless!

In the case of the guard at the tomb my feeling is that we do not have enough info, because this is a singular and very granular event that happened a very long time ago, isn’t supported by truly independent external evidence, and may just as well be an embellishment to a story as a real event of some significance. Rather like the report in the Iliad that Achilles dragged the body of Hector behind his chariot. This may well have happened, in some form or another, or it may just be a fictional embellishment to reinforce a point in the story. We have no way of estimating the likelihood of this specific event from this distance in time.

“Probability Theory” is a big word (two big words, actually). As I said above, we at times can and do assign numbers to our judgements on the likelihood of certain historical events. In this paticular case I’d say that this would not be warranted.

phoodoo,

I think one of the things that’s throwing you (and perhaps Alan) off is the idea that assigning numerical probabilities amounts to claiming a false precision.

For example, you write:

And:

But the numbers in question are often just estimates. When Vincent assigns a 10% value to P(G), he isn’t claiming that 10.1% is too high and 9.9% is too low. He just means that 10% is a reasonable rough estimate. Likewise, when fadedGlory translates “Somewhat unlikely” to 40%, he isn’t claiming that 41% or 39% would be unreasonable.

Note that Vincent’s conclusion is not sensitive to small variations in P(G):

His conclusion is that “P(G|M) is quite unlikely”, not that P(G|M) is some precise number like 13.2%.

I haven’t looked closely enough at Vincent’s argument to see whether I agree with his conclusion about the guard at the tomb, but I definitely agree that probability theory and Bayes’ Theorem can be usefully applied to historical events.

Exactly (!). My Company actually proscribed a table of how the qualitative judgements relate to the numerical probabliity. From memory, it ran like this:

– Impossible: 0%

– Extremely unlikely: 10%

– Very unlikely: 20%

– Unlikely: 30%

– Somewhat Unlikely: 40%

– Equivocal: 50%

and so on towards ‘Guaranteed: 100%’.

We didn’t estimate the numbers, we just read them off the table.

Neil:

There are regularities and tendencies in human behavior, just as there are regularities and tendencies in nature. Suppose you are married with no children, living with your wife in a house with no other occupants. You’ve been happily married for 50 years, and during that time you and she have always been fastidious housekeepers. Your wife is a stable individual with no signs of mental illness.

You come home one evening and find the house in completely disarray, with some valuable items missing. Which of the following two hypotheses is more likely?

a) Your wife flipped out, ransacked her own home, and is now driving to Vegas with the proceeds of the sale of the big screen TV and your Patek Philippe.

b) A burglar broke into your house.

The correct answer is (b), obviously. You might say “Well, that’s just common sense,” and you’d be right. But probability often plays a role in common sense reasoning, and it can be applied to specific events like the ransacking of your home.

faded_Glory,

All jolly fine. Did you get feedback that refined your gut feeling? I imagine there may have been a link between successful prediction and employment prospects. How do we get feedback regarding the presence of guards at Jesus’ tomb or whether Edmund’s Turkish delight was coated in icing sugar.?

@Keiths

You aren’t really supporting your “yes” to my question 1.

Alan,

Sometimes it’s hard, sometimes it’s easy. I find it quite easy to assign a low probability to the mass resurrection story told in Matthew 27:51-53, and easy to defend that judgment. Don’t you?

I think that’s why colewd and fifthmonarchyman have been so skittish since the topic came up. They’ll look ridiculous if they try to defend that fairy tale.

Sorry, fair enough. Scrub previous comment to you.

The question is, is it useful.

Easy to dismiss the whole scenario for me. Remember, I never was indoctrinated.

Why is it necessary to personalise issues?

Sorry but there would be at least one cat.

I’ve had no experience in that regard and am skeptical.

keiths:

Mung:

Same here. But I was responding to Neil, who is okay with a petless existence:

J-Mac:

Neil:

keiths:

Alan:

Yes, of course it’s useful. Imagine being unable to decide that that goofy story is improbable!

Yet by your criteria, we shouldn’t be able to render such a judgment:

keiths:

Alan:

I find it easy to dismiss despite the fact that I was indoctrinated as a child. And that’s how it should be when you’re confronted with a story as improbable as that one.

The alternative explanation — that the story is a dramatic embellishment — is far more probable.

The horror! Would we give it a 50/50 in that case?

Yes, you assert this. What I’m hoping for is a demonstration of how that works with respect to this particular event.

My approach is to immediately discount any aspect of a historical claim that would violate observed reality and examine what is left on the merits. I don’t need probability theory to help me in that endeavour. And neither do you if I understand your “informally” remark correctly.

That is not my position and I am at a loss to understand how you get to that from anything I’ve posted. I’ve simply asked how applying probability theory to this particular scenario we cannot otherwise verify or test helps in deciding the historical accuracy. Please explain.

keiths,

That’s still not math. Those are hunches written in numbers. There is no right or wrong.

Alan Fox,

Most examples of Bayesian inference are about taking previous known sampling, and then applying that to further samples, or calculating odds based on known real percentages (coin tosses for example) then making inferences about coin toss patterns.

I am not sure how much you understand about this, so forgive me if this comes off as condescending. When we say things like “coin tosses” , coins are small pieces of material, usually metal (they often use metal, because its durable, but some also use paper or other materials, but that’s not material right now for this) that are used by many societies as a currency. Toss doesn’t have to mean you actually toss it, like the way you would a baseball or midget, its really more about flipping a two sided piece (like an actual coin if you have seen one) and seeing which sides would fall facing down towards the Earth, and which side would end up facing towards the sky (towards God if you will) , which should be determined by gravity, and the amount of force on the flip, but ultimately we are assuming that no side has a biased towards pointing towards God more than the other side. Its both a physical action, but also a concept of randomness where two outcomes are possible.

You can also use such inferences to determine drug effectiveness and the likely outcomes of the public using some drug. Drugs are things people often ingest or inject into their “body”. The reason for doing so are numerous, but often its because that thing we call a “drug” may well do something to change a condition we refer to as “sick”. (When I say we, I mean scientists of course).

Now how do we make these inferences about drug effectiveness? Well, first we must test the drug, for real, on bodies. Could be rat bodies, could be monkey bodies, could be on bacteria that eat citrate (bacteria is a different kind of body, but don’t worry about that for now) and could be on human bodies-like you. Then after we KNOW how the drug affects helps some bodies with that sick condition, we can make inferences about how more bodies would be affected.

We can use actual numbers here, in these two cases, because we are starting with actual known numbers (like coin tosses or the number of people affected by a drug) and they we are making inferences about those same numbers continuing in the future in relatively similar distributions.

All of this is to say, that it is NOTHING whatsoever like what VJ is talking about. I hope this helps. I am no expert in coin minting, or tossing smaller individuals, so I hope others will weigh in. But if you have more questions I will do my best to answer them for you.

keiths, to Alan:

Mung:

It would be horrible. To make sense of the past and to distinguish myth from truth, judgments of probability are essential.

If you truly had no other basis for a probability estimate, then yes, the rational thing would be to assign a 50% probability. But that would require you to be ignorant of death and biology and the bad habit dead people have of staying dead, among other things.

Here’s an example of a case in which you would truly have no other basis for a probability estimate: Suppose I ask you “Did event E happen?” without giving you any information about event E. You have no idea what E represents, and therefore no reason to favor a “yes” over a “no” or vice-versa. In this situation, the rational thing to do is to assign equal probabilities to the pair. (This is the kind of reasoning that leads to the principle of indifference.)

phoodoo,

Multiplying probabilities together is math, and that’s what faded_Glory and his colleagues do:

It may not produce a ‘hard’ number in this scenario, but multiplication is still math.

Likewise, plugging numbers into Bayes’ Formula and then evaluating it constitutes math. That’s what Vincent Torley and Tim McGrew did:

Your “it’s not math” criticism just doesn’t hold up, phoodoo.

Alan,

I haven’t used that word in this thread.

Earlier you commented:

Again, I haven’t used that word in this thread.

Here’s what I wrote:

So when you write this…

…you are showing that you didn’t understand my comment, which specifically states:

keiths:

Alan:

keiths:

Alan:

And for good reason. Can’t you see the value of being able to judge that the mass resurrection story is extremely improbable?

Alan:

“Violate observed reality?” Setting aside the awkward phrasing, that implies that you would reject any historical claim that describes something that differs from the way we observe it today.

Those “merits” include the likelihood that the claim is true, and likelihood is just an alternate way of expressing probability. Things that are likely have a high probability, and things that are unlikely have a low probability.

You need to gauge likelihood, and that means gauging probability, whether or not you assign a number to it.

keiths:

Alan:

It’s simple, and I quoted the relevant part of your comment:

The mass resurrection story fits those criteria just as the guard posting story does.

We can test our likelihood assessments in both cases by applying our background knowledge. For the mass resurrection claim, the background knowledge would include facts about biology and death. For Vincent’s guard posting argument, it includes things like the fact that falling asleep on guard duty was punishable by death.

A bible scholar like you fell for this?

Good thing you specified the bible translation or I would have never suspected faulplay…You wicked, wicked monkey…😉

Math is not intended as a subjective endeavor. That’s sort of the point of math.

You can stick numbers on things all you want, and call it meaningful, but that doesn’t make it so, and it certainly doesn’t make it math. Math is not simply replacing words with a number. But that is what is being done here.

If I were to argue that you are wrong, based on my math, which states,

-Keiths is known to be emotional=20% likelihood of being wrong.

-I trust Mung more than keiths= 15% likelihood of him being wrong.

-I believe Keiths mother was kind of passive aggressive when she raised keith, that =27% chance of him being wrong.

-I find people with the name Keith to be less reliable when it comes to matters of logic=17.5% likelihood of him being wrong.

-Misc. factors contribute to keiths being wrong, including skeptic title, being from the midwest, etc…=13.4

Conclusion: 92.9% chance Keiths is wrong.

See, I used numbers. But its not really math.

Picking numbers out of the air is not math, because there is no right or wrong.

Oh dear, phoodoo.

You can only add those numbers together if they are mutually exclusive.

You appear to have confused math with arithmetic.

J-Mac, please explain the translation error that brings us the resurrected appearing to many.

https://i.pinimg.com/736x/9b/8d/14/9b8d148fd63797900795ac140bb2a399–hilarious-pictures-funny-images.jpg

Random with respect to God’s physical location then. We ought to be able to build an entire theory of coin tossing on that.

It seems to me that it is the principle of indifference which leads to this kind of reasoning.

If you make up an event ‘E’, and knowing what I know about you, I’d give it a high probability of being entirely fictional. By no means would i give it a 50% probability.

🙂

Mung,

But you must have known [keiths] was not a great fool.

Mung:

Heh. That’s easy to fix:

1. We define C as the outcome of a yet-to-be-done fair coin flip.

3. We define a new event F as follows:

Your job is to specify the (epistemic) probability of F before the coin is flipped.

Jock:

Seconded.

Also, I encourage fifth to give us his interpretation of the passage, so that we can compare it to my supposedly “twisted” interpretation.

phoodoo,

Epistemic probabilities are observer-dependent.

I put a coin in a box and shake it vigorously. Annalise peeks inside the box and sees that the coin landed tails up, but says nothing. Bronwyn doesn’t look inside the box.

I ask Bronwyn, “What is the probability that the coin landed heads up?” She answers “50%”. I ask Annalise the same question, and she answers “Zero.”

Both are correct.

The “twisted” interpretation is possible but I don’t like it…It’s inconsistent with the rest of miracles…

J-Mac,

Please share your interpretation with us.

Also, you didn’t respond to Jock’s request:

While it is not impossible that the exact translation could be accepted, considering that there are many accounts of resurrections in the bible, just like the drinking of poison and surviving the poisonous snakes’ biting, this doesn’t fit the overall theme of miracles…

I emailed a bible scholar about it but he hasn’t responded yet, so I’m going to try to translate it as I think it should be. He knows the original words and stuff, so I can clarify it later, if he agrees with me… 😉 He may not…

“51 At that moment the curtain of the temple was torn in two from top to bottom. The earth shook, the rocks split 52 and the tombs broke open. The bodies of many holy people who had died were raised to life. 53 They came out of the tombs after Jesus’ resurrection and went into the holy city and appeared to many people.

Me

52 and the tombs broke open. The corpses of (holy?) people were thrown out of graves… 53 Other people who had witnessed Jesus resurrection saw the effects of the earthquake and went to the city and told them about it (the signs associated with Jesus death and resurrection)… something like that…

Are you related to Jock DNJTG?

My, that’s weak.

ἠγέρθησαν is used many, many times in Matthew, and the meaning “thrown out of” is entirely lacking.

See, for example, Matt 11:5 — You want to interpret this verse

as

“The dead get throw out of their graves.”

I doubt it. It’s the word Jesus uses to refer to his own resurrection (Matt 16:21) and John the Baptist’s (14:2) too.

J-Mac,

What you produced is a rewrite, not a translation.